Welcome to the final, fifth part of my review for the ACL 2019 conference! You can find previous installments here: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4. Today we proceed to the workshop day. Any big conference is accompanied by workshops. While some people may think that workshops are “lower status”, and you submit to a workshop if you assume you have very little chance to get the paper accepted to the main conference, they are in fact very interesting events that collect wonderful papers around a single relatively narrow topic.

The workshop that drew my attention was the Second Storytelling Workshop, a meeting devoted to a topic that sounded extremely exciting: how do you make AI write not just grammatically correct text but actual stories? This sounded wonderful in theory but in practice, I didn’t really like the papers. I hate to criticize, but somehow it all sounded like ad hoc methods that might bring incremental improvements but cannot bring us close to the real thing. So, for the afternoon session, I went to the NLP for Conversational AI Workshop; there, I was guaranteed some great talks because nearly all of them were invited talks, which are usually delivered by eminent researchers and contain survey-like expositions of their work.

So, for today’s final installment on ACL, I will discuss only two talks from the conference. First, we will work our way through the invited talk at the NLP for Conversational AI Workshop by Professor Yejin Choi. And then we will look at a sample paper from the Second Storytelling Workshop — let’s see if you agree with my evaluation.

The Curious Case of Degenerate Neural Conversation

This was an invited talk by Professor Yejin Choi from the University of Washington (see this link for the slides; all pictures below are taken from there), where she discussed what is missing from all current neural models for natural language generation.

She started by recalling the Alexa Prize that they won in 2017, but even their winning solution was not an end-to-end neural model. Why not? Humans understand language through their understanding of the world. Neural language models lack any knowledge of the world but generate text based on statistical correlations (okay, it’s a bit more complicated but still). The main problem in text generation and conversational AI is to bridge this gap. On the surface, this can be done by introducing long-term coherence to neurally generated text. But deep down, what we really want is to give the models some kind of common-sense understanding about people and the world around us. This is a huge problem and Professor Choi and her group are actually working towards this goal, but it is still very far from a successful resolution.

First, let’s begin with a look at the OpenAI GPT2 model with their famous unicorn example.

Seed (text provided for the model): In a shocking finding, scientist discovered a herd of unicorns living in a remote, previously unexplored valley, in the Andes Mountains. Even more surprising to the researchers was the fact that the unicorns spoke perfect English.

Generated text (continuation, best of 10 tries): The scientist named the population, after their distinctive horn, Ovid’s Unicorn. These four-horned, silver-white unicorns were previously unknown to science.

Now, after almost two centuries, the mystery of what sparked this odd phenomenon is finally solved.

Dr. Jorge Pérez, an evolutionary biologist from the University of La Paz, and several companions, were exploring the Andes Mountains when they found a small valley, with no other animals or humans. Pérez noticed that the valley had what appeared to be a natural fountain, surrounded by two peaks of rock and silver snow.

Pérez and the others then ventured further into the valley. “By the time we reached the top of one peak, the water looked blue, with some crystals on top,” said Pérez.

Pérez and his friends were astonished to see the unicorn herd. These creatures could be seen from the air without having to move too much to see them — they were so close they could touch their horns.

While examining these bizarre creatures the scientists discovered that the creatures also spoke some fairly regular English. Pérez stated, “We can see, for example, that they have a common ‘language,’ something like a dialect or dialectic.”

Dr. Pérez believes that the unicorns may have originated in Argentina, where the animals were believed to be descendants of a lost race of people who lived there before the arrival of humans in those parts of South America.

While their origins are still unclear, some believe that perhaps the creatures were created when a human and a unicorn met each other in a time before human civilization. According to Pérez, “In South America, such incidents seem to be quite common.”

However, Pérez also pointed out that it is likely that the only way of knowing for sure if unicorns are indeed the descendants of a lost alien race is through DNA. “But they seem to be able to communicate in English quite well, which I believe is a sign of evolution, or at least a change in social organization,” said the scientist.

We had never seen neurally generated text of this quality, but note that it still took 10 tries to generate, and there was some random sampling that led to these 10 different tries. If, however, we use beam search instead of random sampling for generation, we get a much stranger text that soon degenerates into a closed loop:

Why does neural text, even in the very best model, degenerate like this? Let’s try different approaches on another example. If we choose the best hypothesis every time, we once again quickly arrive at a closed loop:

Beam search, which looks ahead for a few words, should perform better, right? But in this case, if we use beam search, we only make things worse:

What’s up? Is there a bug? Should we use a bigger beam? Wider, longer? Nope, larger beams don’t help. You can try it for yourself. If you compare human language and machine-generated language, you will see that the conditional probabilities of each subsequent topic are very high for machine-generated texts (beam search is the orange line below) but this is definitely not the case for humans (blue line):

The same effect happens in conversational models. The famous “I don’t know. I don’t know. I don’t know…” answer that plagues many dialogue systems actually has a very high likelihood of occuring, and it gets more probable with each repetition! The loop somehow reinforces itself, and modern attention-based language models easily learn to amplify the bias towards repetition.

On the other hand, humans don’t try to maximize the probability of the next word — that would be very boring! The natural distribution of human texts shown above has a lot of spikes. We are trying to say something, provide information, express emotions.

So what do we do? We can try to sample randomly from the language model distribution. In this case, we begin OK but then quickly degenerate into gibberish. Follow the white rabbit:

This happens because current language models do not work well on the long tail of all words. One uncommon word generated at random from the long tail, and everything breaks down. One way to fix this is to use top-k sampling, i.e., sample randomly but only from the best k options. In our experiments, we no longer get any white rabbits and the text looks coherent enough:

There are still two problems, though. First, there is really no easy way to choose k. The number of truly plausible continuations for a phrase naturally depends on the phrase itself. If k is too large we will get white rabbits, and if k is too small we will get a very bland, boring and possibly repetitive text.

So the next idea is to use top-p sampling, sampling only from the nucleus of the distribution that adds up to a given total probability of say 90% or 95%. In this case, top-p sampling gets some very good results, much more exciting but still coherent enough:

Then Professor Choi talked about GROVER, a recent work from her lab (Rowan Zellers is the first author) that has a huge model with 1.5B parameters able to generate missing variables from the (article, domain, title, author). That is, write an article for a given title, written in the style of a particular author, generate titles from texts, and so on. I won’t go into the details here — GROVER well deserves a separate NeuroNugget, and excellent posts have already been written about it (see, e.g., here). For the purposes of this exposition, let’s just note that GROVER also uses nucleus sampling to generate the wonderful examples that can be found and even generated anew with a demo here.

Nucleus sampling and top-k sampling can also be evaluated in the context of conversational models. Professor Choi actually talked about the Conversation AI 2 challenge, and even made a mistake: she said that the HuggingFace team whose model they used for experiments won the competition, while it was actually us who won (see my earlier post on this). Well, I guess in the large scheme of things it does not matter: our paper at ACL is already a joint effort with HuggingFace, and we hope to keep the collaboration going in the future. As for the comparison, neither top-k nor nucleus sampling was really enough to get an interesting conversation going for a long time.

One way to proceed would be to devise models that extract the intent of the speaker from an utterance — finding the reason for the utterance, the desired result, the effect that this might have on the other speakers etc. This work is already underway in Prof. Choi’s lab and they have published a very interesting paper related to it called ATOMIC: An Atlas of Machine Commonsense for If-Then Reasoning. It contains an actual atlas (you could call it a knowledge base) of various causes, effects, and attributes. Here is a tiny subset:

In total, ATOMIC is a graph with nearly 900K commonsense “if-then” rules like the ones above. This is probably the first large-scale effort to collect such information. There are plenty of huge knowledge bases in the world, but they usually contain taxonomic knowledge, knowledge of “what” rather than “why” and “how”, and ATOMIC begins to fill in this gap. It contains the following types of relations:

Building on ATOMIC, Prof. Choi and her lab proceeded to create a model that can construct such commonsense knowledge graphs. This would be, of course, absolutely necessary to achieve true commonsense reasoning: you can’t crowdsource your way through every concept and every possible action in the world.

The result is a paper called “COMET: Commonsense Transformers for Automatic Knowledge Graph Construction”. With a Transformer-based architecture, the authors produce a model that can even reason about complex situations. Here is a random sample of COMET’s predictions, with the last column showing human validation of plausibility:

Looks good, right? And here are some predictions for causes and effects for the phrase “Eric wants to see a movie”, answering the question — ‘Why would that be?’

and, ‘What would be the effect if Eric got his wish?’

Models like this suggest that we can try to write down declarative knowledge like this and have a fighting chance of constructing models that, somewhat surprisingly, are able to generalize well to previously unseen events and achieve near-human performance. Will this direction lead to true understanding of the world around us? I cannot be sure, of course, and neither can Professor Choi. But some day, we will succeed in making AI understand. Just you wait.

A Hybrid Model for Globally Coherent Story Generation

And now let us switch to a sample presentation from the Storytelling Workshop. Zhai Fangzhou et al. (ACL Anthology) presented a new model for generating coherent stories based on a given agenda. What does this mean? Natural language generation is basically the procedure of translating semantics into proper language structures, and a neural NLG system will usually consist of a language model and a pipeline that establishes how well and how fully the language structures we generate reflect the semantics, i.e., what we want to say. One example is the Neural Checklist model (Kiddon et al., 2016) where a checklist keeps track of the generation process (have we mentioned this yet?), and another is the Hierarchical seq2seq (Fan et al., 2019, actually presented right here at the ACL 2019).

The model by Fangzhou et al. tries to generate coherent stories about daily activities. It has a symbolic text planning component where you write scripts that reflect standardized sequences of events about daily activities. A script is a graph that reflects how the story should progress. It contains events that detail these daily activity scenarios, and the corpus for training contains texts labeled (through crowdsourcing) with these events. Here is a sample data point:

This kind of labeling is hard, so, naturally, the labeled dataset is tiny, about 1000 stories. Another source of data are the temporal script graphs (TSG) that arrange script events according to their temporal and/or causal order. Here is a sample TSG for baking a cake:

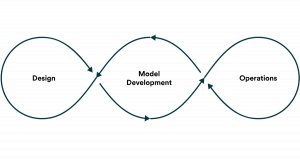

So the proposed model would have an agenda (a sequence of events that plans the story), and the NLG part attends to the most relevant events and decides whether the current event has been annotated and if we can proceed to the next one. In general, it looks like this:

How do you implement all this? Actually, it’s rather straightforward: you use a language model and condition it on the embeddings of currently relevant events. Here is the general scheme:

Let’s see what kind of stories this model can generate. Here is a comparison of several approaches, with the full model in the last place. It is clear that the full model is indeed able to generate the most coherent story that best adheres to the agenda:

These improvements are also reflected in human evaluations: agenda coverage, syntax, and relevance of the full model approach, but still remain below the marks given by human assessors to human-written stories.

In general, this is a typical example of what the Second Storytelling Workshop was about: it looks like good progress is being made, and it seems quite possible to achieve perfection with this kind of story generation quite soon. Add a better language model, label a larger dataset by spending more time and money on crowdsourcing, improve the phrase/event segmentation part, and the result should be virtually indistinguishable from human stories that are similarly constrained on a detailed agenda. But it is clear that this approach can only work in very constrained domains, and what you can actually do with these stories is quite another matter…

Sergey Nikolenko

Chief Research Officer, Neuromation